Chesters fort (CILVRNVM)

Chesters is important for many reasons, not least as the house (The Chesters) was the home of John Clayton. In the 19th century, he was one of the leading lights in the conservation of the central sector of the Wall. The happy coincidence of the Military Road choosing to avoid the crags between Wall Miles 34 and 45 and Clayton owning the estate that included that stretch, combined with his passion for archaeology, meant that this part of the Wall at least received more care and attention than it had since Roman times. Elsewhere, at that time, landowners and tenants were still merrily grubbing it up and, as we have seen, even dynamiting it in some extreme cases. Any suggestion that the curtain wall might have survived in any substantial form had the Military Road not been built is, at best, debatable (and, as we shall see later, the road ironically helped preserve the wall in places).

Chesters is important for many reasons, not least as the house (The Chesters) was the home of John Clayton. In the 19th century, he was one of the leading lights in the conservation of the central sector of the Wall. The happy coincidence of the Military Road choosing to avoid the crags between Wall Miles 34 and 45 and Clayton owning the estate that included that stretch, combined with his passion for archaeology, meant that this part of the Wall at least received more care and attention than it had since Roman times. Elsewhere, at that time, landowners and tenants were still merrily grubbing it up and, as we have seen, even dynamiting it in some extreme cases. Any suggestion that the curtain wall might have survived in any substantial form had the Military Road not been built is, at best, debatable (and, as we shall see later, the road ironically helped preserve the wall in places).

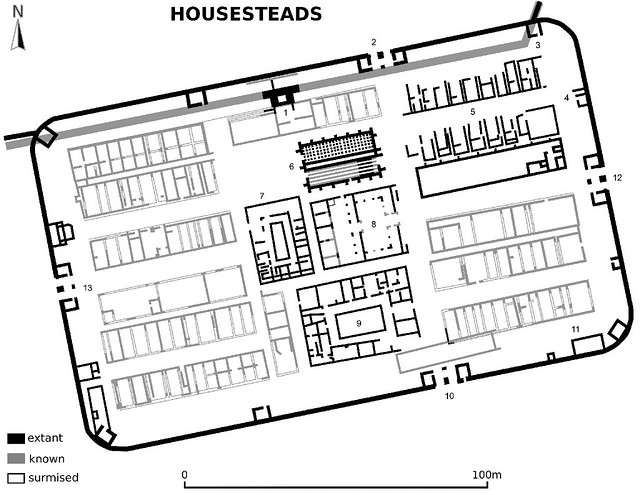

The fort itself is 5.6km (3.5 miles) from Carrawburgh and is 2.3ha (5.75 acres) in area. It sits astride the Wall and needed two extra gateways (instead of the usual four) to accommodate this inconvenience. Within the fort, the remains of the commanding officer’s house and the headquarters building (including its subterranean strongroom) are on display, as is a pair of cavalry barracks. Down by the river North Tyne are the remains of the fort bath-house, preserved to an impressive height by hillwash. Naturally, John Clayton set about excavating parts of the fort. Set in formal parkland, it can now look rather lush and incongruous in comparison with the bleak upland site at Housesteads, which he also owned.

The fort itself is 5.6km (3.5 miles) from Carrawburgh and is 2.3ha (5.75 acres) in area. It sits astride the Wall and needed two extra gateways (instead of the usual four) to accommodate this inconvenience. Within the fort, the remains of the commanding officer’s house and the headquarters building (including its subterranean strongroom) are on display, as is a pair of cavalry barracks. Down by the river North Tyne are the remains of the fort bath-house, preserved to an impressive height by hillwash. Naturally, John Clayton set about excavating parts of the fort. Set in formal parkland, it can now look rather lush and incongruous in comparison with the bleak upland site at Housesteads, which he also owned.

The best strategy for a visit to Chesters is to see the site first and then do the museum, but you do what you feel most comfortable with, and you may find the weather dictates your course of action (and the English Heritage tea shop is a handy retreat for the peckish). For our purposes, it is the fort first.

Unlike any of the other forts we have seen to the west, Chesters does not cower meekly behind the line of the curtain wall but in fact boldly protrudes to the north. This provided an unusual challenge to its constructors since, if they used the usual pattern of four gateways, one side (either north or south) would end up with three gateways, the other only one. They opted to give it an extra two ‘minor’ single-portalled gates to the south of the wall and have three twin-portalled ones to the north of it.

Any tour of the fort will begin at the north gate, to which the path from the museum leads you. This is the porta praetoria, the main gate facing northwards and, importantly (and unlike Housesteads), facing the enemy. A twin-portalled gateway, as you might expect, this was the main one facing into Barbaricum. There is a very obvious stone-lined channel under the western carriageway – drains and aqueducts nearly always left and entered forts at the gates (although Housesteads has already presented us with one exception to that rule). This example, however, is the aqueduct bringing water into the site (the main sewer carrying it out passed out through the slightly lower east gate, as we shall see). The aqueduct channel seems to have followed the contours round Lincoln Hill to get to the fort, with its source reported to be further up the valley of the North Tyne (although this has not been tested by excavation). An inscription of around AD 180 records the construction of an aqueduct, although we have to presume the garrison didn’t spend the best part of half a century without water, so it may have been an additional one or a replacement.

Having admired the north gate (the usual two portals, one later blocked, with flanking guardrooms) we can head off across the fort (there is usually a mown strip to guide us) towards the west gate, noting as we pass it a short length of the western curtain wall of the fort before we reach our goal. Adjacent to the south tower we can see the junction of Hadrian’s Wall with the fort, confirming that this west gate lay north of the wall. The curtain wall was in fact constructed before the fort and had to be dismantled to insert the fort. The usual features are present (threshold blocks with door stops, pivot holes, large opus quadratum blocks in the spina and inserted into the guard chamber walls) so we may note those and move on.

Having admired the north gate (the usual two portals, one later blocked, with flanking guardrooms) we can head off across the fort (there is usually a mown strip to guide us) towards the west gate, noting as we pass it a short length of the western curtain wall of the fort before we reach our goal. Adjacent to the south tower we can see the junction of Hadrian’s Wall with the fort, confirming that this west gate lay north of the wall. The curtain wall was in fact constructed before the fort and had to be dismantled to insert the fort. The usual features are present (threshold blocks with door stops, pivot holes, large opus quadratum blocks in the spina and inserted into the guard chamber walls) so we may note those and move on.

The path next takes us to the south-western interval tower (the western minor gate and the south-western corner tower have not been uncovered for display) where we can see that, unlike the turrets on Hadrian’s Wall, this fort tower has a central doorway at its base. We may briefly admire the eavesdrip channel along the base of the tower before trotting on towards our next gate (there are six, don’t forget). We can move on to the south gate, another twin-portalled structure, but this one still retaining traces of its blocking. Propped up against it is a large monolithic slab with a central lewis hole and two pivot holes, one of them intact. This is an example of an upper pivot stone, designed to sit above the spina and receive the upper pivots of the gate leaf on either side of it.

The path next takes us to the south-western interval tower (the western minor gate and the south-western corner tower have not been uncovered for display) where we can see that, unlike the turrets on Hadrian’s Wall, this fort tower has a central doorway at its base. We may briefly admire the eavesdrip channel along the base of the tower before trotting on towards our next gate (there are six, don’t forget). We can move on to the south gate, another twin-portalled structure, but this one still retaining traces of its blocking. Propped up against it is a large monolithic slab with a central lewis hole and two pivot holes, one of them intact. This is an example of an upper pivot stone, designed to sit above the spina and receive the upper pivots of the gate leaf on either side of it.

What is a lewis hole? They were used on large blocks of stone to enable them to be lifted with sheer legs. A three-part wedge with a central removable shackle (known as a three-legged lewis or St Peter’s Keys) was inserted into a splayed rectangular hole in the stone which, when the middle component was inserted, would lock in place to be lifted. It is a characteristic Roman technique, not seem before and seldom afterwards in Britain.

What is a lewis hole? They were used on large blocks of stone to enable them to be lifted with sheer legs. A three-part wedge with a central removable shackle (known as a three-legged lewis or St Peter’s Keys) was inserted into a splayed rectangular hole in the stone which, when the middle component was inserted, would lock in place to be lifted. It is a characteristic Roman technique, not seem before and seldom afterwards in Britain.

Moving on, we pass another interval tower before reaching the corner tower, located in the centre of the rounded south-east corner of the fort wall. Unlike interval and gate towers, corner towers tended to be wedge-shaped, so that their side walls met the curtain wall at a tangent in either case. It is less noteworthy that this too has a central doorway.

Moving on, we pass another interval tower before reaching the corner tower, located in the centre of the rounded south-east corner of the fort wall. Unlike interval and gate towers, corner towers tended to be wedge-shaped, so that their side walls met the curtain wall at a tangent in either case. It is less noteworthy that this too has a central doorway.

Now we head north along the east defences and reach the only minor gate that is displayed. This, as mentioned above, was a single-portal gateway which gave access to the area south of the Wall and specifically to the civil settlement and the baths. Note that in its surviving form, there are two gate leaves (one pivot hole on either side) with a central stop block.

Now we head north along the east defences and reach the only minor gate that is displayed. This, as mentioned above, was a single-portal gateway which gave access to the area south of the Wall and specifically to the civil settlement and the baths. Note that in its surviving form, there are two gate leaves (one pivot hole on either side) with a central stop block.

And so to the last gateway, the main east gate. Here we can see a main drain passing out through the southern portal, but it is of course north of the wall, so not destined for the bath-house. The northern gate tower has been constructed over the backfilled (with rubble) ditch of the original version of Hadrian’s Wall. Both portals ended up being blocked and the lack of wear on the threshold blocks suggests neither were very heavily used. So much for all that effort to add extra gates.

And so to the last gateway, the main east gate. Here we can see a main drain passing out through the southern portal, but it is of course north of the wall, so not destined for the bath-house. The northern gate tower has been constructed over the backfilled (with rubble) ditch of the original version of Hadrian’s Wall. Both portals ended up being blocked and the lack of wear on the threshold blocks suggests neither were very heavily used. So much for all that effort to add extra gates.

After this heady tour of the defences and an orgy of towers and gates, it is time to turn our attention to the internal buildings that are there to be inspected. The first will be the commanding officer’s house (praetorium), the nearest and most perplexing of the structures, given the welter of inserted hypocausts, varying floor levels, and different styles of construction. If we enter it through the little gate next to the tree, we are immediately able to admire the finely moulded decorated plinth course on the north-east corner of the structure. Just to the south are some brick pilae from one of the many heating systems, but if you are willing to take a few paces even further south you will find an excellent example of a brick-arched flue through the east wall. Don’t worry, we’ll wait. We will next move a little to the west to see another heated room with a raised threshold, showing the level the commanding officer actually lived at, with all this heating technology at his disposal. Note how the threshold block is worn smooth in the middle and that there are two rectangular recesses on either side to receive the upright stone jambs, now missing. Doubtless you will already have spotted the channel leading to the socket for the door pivot. We will carry on moving westwards and make a left turn towards where the courtyard ought to be. The floor levels are still raised to either side of us and it becomes apparent that the standard courtyard-style praetorium has here been subverted in the later period, with additional rooms being added in the courtyard space. If we turn right we can now head west again, across where the courtyard would have been, and make for the headquarters building (principia).

After this heady tour of the defences and an orgy of towers and gates, it is time to turn our attention to the internal buildings that are there to be inspected. The first will be the commanding officer’s house (praetorium), the nearest and most perplexing of the structures, given the welter of inserted hypocausts, varying floor levels, and different styles of construction. If we enter it through the little gate next to the tree, we are immediately able to admire the finely moulded decorated plinth course on the north-east corner of the structure. Just to the south are some brick pilae from one of the many heating systems, but if you are willing to take a few paces even further south you will find an excellent example of a brick-arched flue through the east wall. Don’t worry, we’ll wait. We will next move a little to the west to see another heated room with a raised threshold, showing the level the commanding officer actually lived at, with all this heating technology at his disposal. Note how the threshold block is worn smooth in the middle and that there are two rectangular recesses on either side to receive the upright stone jambs, now missing. Doubtless you will already have spotted the channel leading to the socket for the door pivot. We will carry on moving westwards and make a left turn towards where the courtyard ought to be. The floor levels are still raised to either side of us and it becomes apparent that the standard courtyard-style praetorium has here been subverted in the later period, with additional rooms being added in the courtyard space. If we turn right we can now head west again, across where the courtyard would have been, and make for the headquarters building (principia).

As at Housesteads, the HQ has entrances on either side as well as its main northern one, these side entrances apparently serving more than one purpose. The one nearest the praetorium would certainly provide a useful short cut for the commanding officer, but the threshold of this eastern doorway shows clear evidence of wheel ruts, implying that carts were driven into the building on a regular basis. You may well wonder why this might have been. Let us enter the structure through the door and enter the cross-hall, noting the dais (the tribunal) ahead of us (this one clearly had a hatch underneath it; what were they storing there? And was it brought in with carts?).

As at Housesteads, the HQ has entrances on either side as well as its main northern one, these side entrances apparently serving more than one purpose. The one nearest the praetorium would certainly provide a useful short cut for the commanding officer, but the threshold of this eastern doorway shows clear evidence of wheel ruts, implying that carts were driven into the building on a regular basis. You may well wonder why this might have been. Let us enter the structure through the door and enter the cross-hall, noting the dais (the tribunal) ahead of us (this one clearly had a hatch underneath it; what were they storing there? And was it brought in with carts?).

To our left, in the range of offices, is a magnificent, vaulted underground strong room, where the unit savings would be kept (perhaps the carts were moving money around!). Mileage may vary as to whether we may enter it (sometimes it is flooded), but note how small the steps are (best to go down with your feet sideways) and the large monolithic stone jambs used here. When we are done here, we can head across the courtyard again and enter the courtyard. As ever, we find a peristyled rectangular yard with an eavesdrip running round it, indicative of a pent roof, and over in the north-west corner is a well (which still often contains water) which is worth inspecting.

A few moments may be devoted to pondering the well and its sacred significance before turning to face the south and the rear range of offices, where the standards would be kept. Look down at the paving on the western side of the courtyard. There, on a large circular boss, is one of the largest phallic symbols to be found anywhere on Hadrian’s Wall. This seems like a formidable apotropaic insurance policy. Now we can turn and head northwards, out of the main entrance of the HQ, and towards the barrack buildings ahead of us.

A few moments may be devoted to pondering the well and its sacred significance before turning to face the south and the rear range of offices, where the standards would be kept. Look down at the paving on the western side of the courtyard. There, on a large circular boss, is one of the largest phallic symbols to be found anywhere on Hadrian’s Wall. This seems like a formidable apotropaic insurance policy. Now we can turn and head northwards, out of the main entrance of the HQ, and towards the barrack buildings ahead of us.

Before entering the barracks enclosure, we should pause and note that not all of the barrack buildings are on display. Only five of the contubernia, the rooms in which the men were accommodated, are now uncovered, at least three more remaining buried beneath our feet. In front of us are two symmetrically arranged buildings, each with officers’ quarters at the far end and a verandah (continuing the roofline) in front of the men’s rooms. A central drain (originally covered) runs along the centre and fragments of columns can be seen (although Gibson’s photographs of the first excavations suggests things have moved around a bit since the 19th century). The barrack rooms housed the men, possibly with a central timber partition separating a front storage area from the rear sleeping area, whilst the end rooms would house the decurio who commanded each turma of cavalry (nominally 32 men) and his NCOs, including his deputy (the duplicarius, on double pay), the standard bearer (signifer), and the sesquiplicarius (on one-and-a-half times pay!). Before we leave the barracks, we need to do a quick calculation. Remember that there are eight men to a room and 32 to a turma? If we have at least eight rooms to a barrack, then it is likely that each building housed two turmae and that the officer’s quarters at the east end were duplicated at the unexcavated west end, making a double-ended barrack (we know of such structures from other cavalry forts elsewhere in the empire). After all that maths, we may well feel that we could do with relaxing in the fort bath-house. Fortunately, Chesters has one of the best preserved.

Before entering the barracks enclosure, we should pause and note that not all of the barrack buildings are on display. Only five of the contubernia, the rooms in which the men were accommodated, are now uncovered, at least three more remaining buried beneath our feet. In front of us are two symmetrically arranged buildings, each with officers’ quarters at the far end and a verandah (continuing the roofline) in front of the men’s rooms. A central drain (originally covered) runs along the centre and fragments of columns can be seen (although Gibson’s photographs of the first excavations suggests things have moved around a bit since the 19th century). The barrack rooms housed the men, possibly with a central timber partition separating a front storage area from the rear sleeping area, whilst the end rooms would house the decurio who commanded each turma of cavalry (nominally 32 men) and his NCOs, including his deputy (the duplicarius, on double pay), the standard bearer (signifer), and the sesquiplicarius (on one-and-a-half times pay!). Before we leave the barracks, we need to do a quick calculation. Remember that there are eight men to a room and 32 to a turma? If we have at least eight rooms to a barrack, then it is likely that each building housed two turmae and that the officer’s quarters at the east end were duplicated at the unexcavated west end, making a double-ended barrack (we know of such structures from other cavalry forts elsewhere in the empire). After all that maths, we may well feel that we could do with relaxing in the fort bath-house. Fortunately, Chesters has one of the best preserved.

Exit the barracks, head east past the east gate and down the hill, pausing on the way to examine a short length of Hadrian’s Wall that is exposed. Excavation a little further to the east, between here and the river, found that the first clay-bonded wall collapsed spectacularly and had to be rebuilt with mortar.

Exit the barracks, head east past the east gate and down the hill, pausing on the way to examine a short length of Hadrian’s Wall that is exposed. Excavation a little further to the east, between here and the river, found that the first clay-bonded wall collapsed spectacularly and had to be rebuilt with mortar.

Carry on down the hill to the enclosure containing the baths. Before entering, you can appreciate how the hill-wash, the soil moved downhill with time, has helped protect the building, since the tops of the standing walls reflect the profile of the hillside leading down to the riverbank.

Down the steps, we enter through the porch to the changing room, the apodyterium, with its niches which may have held the bathers’ clothes (although there is a view that these were niches for statues of divinities). In a small delve next to the niches you can see the original floor level, revealing that the low ledge there was in fact originally a bench, perhaps lending credence to the clothes storage hypothesis. We can now move southwards and immediately turn right and right again to look at the sudatorium, the Ridiculously Hot Room (it had its own heating system under it, separate from the main baths).

Down the steps, we enter through the porch to the changing room, the apodyterium, with its niches which may have held the bathers’ clothes (although there is a view that these were niches for statues of divinities). In a small delve next to the niches you can see the original floor level, revealing that the low ledge there was in fact originally a bench, perhaps lending credence to the clothes storage hypothesis. We can now move southwards and immediately turn right and right again to look at the sudatorium, the Ridiculously Hot Room (it had its own heating system under it, separate from the main baths).

This is particularly interesting as it has more surviving examples of monolithic stone door jambs, as well as a fine example of a worn threshold similar to the ones we saw in the CO’s house, complete with pivot hole and location slot. Back out of this balneal cul-de-sac and turn right into the main bathing area, with the warm room (tepidarium) and then the hot room (caldarium). We are actually standing at the level of the base of the hypocausts, the floor level being betrayed by a threshold block to our left.

This is particularly interesting as it has more surviving examples of monolithic stone door jambs, as well as a fine example of a worn threshold similar to the ones we saw in the CO’s house, complete with pivot hole and location slot. Back out of this balneal cul-de-sac and turn right into the main bathing area, with the warm room (tepidarium) and then the hot room (caldarium). We are actually standing at the level of the base of the hypocausts, the floor level being betrayed by a threshold block to our left.

Before we go any further, turn round and look at the step we just came down to get here: it a curiously shaped stone. This in fact a voussoir made of tufa (light and fire-resistant), just one remaining component of a series of arches that ran along the length of the baths, slotted to hold thin bricks between these ribs and thus provide hollow tubes through which warm air (which was carried up the walls from the heating below) could also heat the roof space. All clever stuff.

Now we can move towards the south end, noting the hot plunge bath to our right and, behind it, the remains of a window through the wall. The south end contained the area where the fire actually burnt, beneath a large bronze water tank (now long gone), to provide the hot water for the plunge. We may sneakily pass out of here through the flue, noting as we go that there was a second bathing suite immediately to the east, and then we can turn left and left again to take us along the eastern side of the exterior of the building, buttressed for extra strength, to the latrines at the far end.

This area has been heavily damaged by the river in the past, before it was ever excavated, but we can make out the sewer channel running around the seating area, whilst down to the right, nearer the riverbank, are examples of opus quadratum with their increasingly familiar lewis holes. We can finish with the baths by heading back along the path, around the exterior of the building, and back up the stairs. Now it is time to leave the fort, but if you haven’t already inspected it, this is your cue to visit the museum.

This area has been heavily damaged by the river in the past, before it was ever excavated, but we can make out the sewer channel running around the seating area, whilst down to the right, nearer the riverbank, are examples of opus quadratum with their increasingly familiar lewis holes. We can finish with the baths by heading back along the path, around the exterior of the building, and back up the stairs. Now it is time to leave the fort, but if you haven’t already inspected it, this is your cue to visit the museum.

John Clayton’s son Nathaniel formed a small museum at Chesters (still lovingly tended in as near its original condition as possible) just before the First World War, housing the family collection of artefacts and inscriptions garnered not just from Chesters but from all the sites within the original Clayton estate, including Housesteads, Vindolanda, Great Chesters, and Carrawburgh. Its lapidarium is truly impressive, with rows of altars, milestones, and sculpture, and shelves of lesser stonework, including building stones from the Wall. It is worth devoting some time to and there is a treat awaiting in the back room, where some of Ronald Embleton’s original reconstruction paintings, undertaken for H. Russell Robinson’s book What the Soldiers Wore on Hadrian’s Wall, are hanging. The museum has only recently been refurbished and relit (a process that required the careful rehousing of a colony of bats) and is a splendid example of what can be achieved, and a far cry from when one of the past curators complained about the birds flying around the main gallery and leaving their calling cards on the cases.

The garrisons of Chesters included the cohors I Delmatarum in the 2nd century and the ala II Asturum from the early 3rd onwards. The latter originated in Asturia, in what is now Spain. It has been pointed out that the name Cilurnum may owe something to a people called the Cilurnigi from that same area of Spain. You could say that this is a little bit of Northumberland that is forever Spain.

The garrisons of Chesters included the cohors I Delmatarum in the 2nd century and the ala II Asturum from the early 3rd onwards. The latter originated in Asturia, in what is now Spain. It has been pointed out that the name Cilurnum may owe something to a people called the Cilurnigi from that same area of Spain. You could say that this is a little bit of Northumberland that is forever Spain.

You must be logged in to post a comment.