The Corbridge Hoard

In 1964, the Durham/Newcastle University training excavation at Corbridge revealed one of the most important finds to come from Northern Britain (no hyperbole here, of course… well, not much): a large wooden chest containing a variety of objects. In many respects, despite its final publication in 1988, it remains a forgotten treasure. Certainly, one of its components – some sets of articulated Roman plate armour – went on to become very famous and provide the basis for countless reconstructions of the type of defence known as ‘lorica segmentata‘ (the name is a 16th-century invention coined to describe this type of armour where it was depicted on Trajan’s Column in Rome). However the other finds have tended to get overlooked, possibly because there was no precious metal, so let’s try and redress the balance a little with this Brief Guide to the Corbridge Hoard.

M for mineralisation

The natural sands and gravels of the river terrace at Corbridge are not very conducive to organic survival, under normal circumstances, but the huge amount of ferrous material in the Corbridge Hoard allowed something akin to fossilisation to take place, affecting the box and all its contents. This is mineralisation, whereby the cell structure of the organic components was replaced by minerals leached from the corroding iron and steel. Thus things that do not normally survive in the archaeological record without anaerobic conditions (wood, leather, feathers and so on) were found in the Hoard.

The chest

Analysis showed that the box containing the Hoard had been made of alder wood, a species that normally grows in damp areas and typically the sort of timber cleared for a riverside site like Corbridge. Thus it is possible this was constructed when this (or conceivably another) fort was first built (the first fort at Carlisle was partly built from alder). The planks of the chest were carefully dovetailed at the corners and it had clearly been more than just a crate in its heyday: it was covered in leather, hinting at a degree of luxury. It was 0.88m long and 0.58m wide and up to 0.41m high. The chest was hinged, had a lock plate, and had iron reinforcements on each corner.

The armour

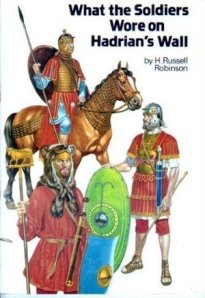

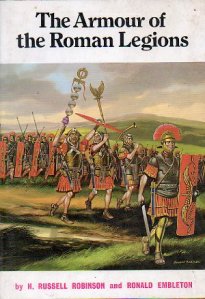

The armour was painstakingly pieced together by Charles Daniels and its interpretation aided by collaboration with Henry Russell Robinson of the Tower of London Armouries. Every re-enactor wearing ‘lorica segmentata‘ today owes them a great debt of gratitude. Consisting of six non-matching top units in three pairs and three equally disparate lower pairs, it is a curious mix (more for what it implies about the missing halves than what is actually there). Frequently repaired in the past it was in the process of being cannibalised again. Quite apart from allowing us to understand the structure of this type of armour, it is an exquisitely frank document of combat, vicious, brutal, and prolonged.

The weapons

The chest contained several bundles of spearheads, tied together with cord, fragments of their wooden shafts still in the sockets. Again, these were weapons that had been broken in combat and were in need of re-shafting.

The tools

A saw, a pickaxe, a chisel, a crow-bar, shears, and a knife were included in the Hoard, along with a variety of nails and carpentry fittings. These are all the sort of things that would be found in a workshop.

The writing tablets and papyrus

Everybody knows of the wooden ink writing tablets from Vindolanda, but there were re-usable wax tablets from there too and the Corbridge Hoard also contained some of the latter. Of even more interest were the tiny fragments of papyrus, hinting at long-vanished bureaucracy on a foreign medium.

The feathers

The feathers were a curious addition. Do they represent cushions or perhaps plumes from helmets? We have no way of knowing and can only note the rich variety of material stowed within this chest.

The other stuff

A large tankard, a scapula (possibly modified as a scoop), a pulley, an uneven number of gaming counters, and a crusie (a wrought iron lamp holder, virtually identical to 19th-century examples) were amongst the numerous odds and end that seem to have been thrown into the box.

The dating

Examination of the stratigraphy of the find showed that it had been buried at the end of occupation of either the second or third phase of occupation (AD 122–38) and thus belonged within the Hadrianic period. In this respect, the signs of combat amongst the material within the Hoard are intriguing and later matched by finds of the same period from Carlisle, as we shall see.

The purpose

What was it for? Our best guess is that it was a selection of stuff (junk would be too harsh a word, although probably quite near the mark) hanging around in a workshop awaiting repair or re-use. Then, when the time came to abandon the fort, it was simply buried to save having to take it away and keep the raw materials from falling into the hands of an enemy.

***

It will soon be the 50th anniversary of the discovery of the Hoard and English Heritage have just mounted a new display of the items from the chest in July 2012, including film footage shot by Charlie Anderson during the excavation.

To find out more about Roman Corbridge and enjoy your personalised (and not-too-unfriendly) tour of the site, see the sections of the blog dealing with the buildings north of the Stanegate, the eastern legionary compound, and the western legionary compound.

You must be logged in to post a comment.