There were, at various times, something like 2,500 cavalry along the line of Hadrian’s Wall within the alae and cohortes equitatae that made up its garrison.* Every man jack of them would have known the significance of a face-mask helmet, and at least 170 (perhaps more) of them will have owned one.

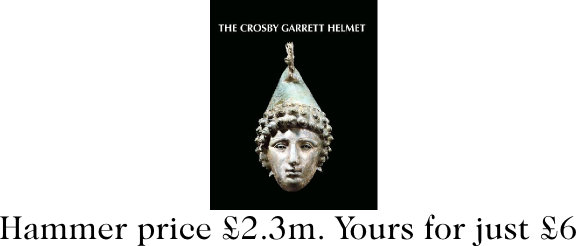

The 2013/14 exhibitions of the Crosby Garrett cavalry sports helmet at (first) Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery in Carlisle and (subsequently) the British Museum have inevitably disturbed the dust on a question that is occasionally aired, battered to within an inch of its life with a few facts, only to revive, zombie-like after a respectable interval: did Roman cavalry wear face-masks in battle?

The 2013/14 exhibitions of the Crosby Garrett cavalry sports helmet at (first) Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery in Carlisle and (subsequently) the British Museum have inevitably disturbed the dust on a question that is occasionally aired, battered to within an inch of its life with a few facts, only to revive, zombie-like after a respectable interval: did Roman cavalry wear face-masks in battle?

Let’s begin by looking at some of those facts before we move on to what I regard as a decisive consideration that tends to get overlooked.

Arrian

Arrian

In his description of the elaborate exercises practised by the Roman auxiliary cavalry he called the Hippika Gymnasia, the historian, military commander, and friend of Hadrian was very clear about the use of face-mask helmets.

2. The riders themselves, according to rank or because they distinguish themselves in horsemanship, set off with golden helmets of iron or bronze, in order to attract the attention of onlookers by this means. 3. Unlike battle helmets, these defend not only the head and cheeks but, conforming to the faces of the riders, have openings for the eyes which do not hinder the vision and yet offer protection.

Burials

A number of burials from around the Roman Empire seem to have belonged to members of tribal elites who had served with Roman auxiliary cavalry units. Unusually (because it was not normal practise for Roman soldiers to do so), these included full panoplies of equipment. The recovery of both battle and face-mask helmets from burials like those at Chatalka in Bulgaria and Nawa in Syria demonstrate that both types of helmet were in use at the same time.

Tombstones

The funerary monuments of Roman cavalrymen are a vital source of information for understanding their dress and equipment, particularly in the 1st century AD. These usually show the deceased helmeted and almost invariably depict the helmet as being equipped with cheek-pieces. Some superb examples where the cheek-pieces of the rider’s helmet are unmistakeable come from the Rhineland, including T. Flavius Bassus from Köln and C. Romanius Capito from Mainz-Zahlbach, both of the ala Noricorum.

Examples from Britain with similarly unambiguous cheek-pieces include Longinus Sdapeze of the ala I Thracum from Colchester (whose face was probably knocked off in the Boudican rebellion and only recently found and re-attached) and the slightly ghoulish depiction of Insus of the ala Augusta from Lancaster, brandishing the severed head of his foe.

Why are the cheek-pieces so important? Because only one of the known cavalry sports helmets depicts them on the sides of the face-mask (the helmet from Vize in European Turkey, now in Istanbul Archaeological Museum). All the others show an idealised face surrounded by curls of hair. Thus, if the tombstones were intended to show face-mask helmets, it might be anticipated that cheek-pieces would not be depicted.

Field of vision

An important – and I believe crucial – consideration that tends to get overlooked is that of peripheral vision. Helmets with some form of face-mask, such as Viking or Saxon examples, or even Corinthian helmets from the Classical Greek period, typically incorporate eye apertures that allowed for the largest possible field of view for the wearer. Cavalry sports helmets, on the other hand, by seeking to imitate the human eye, deliberately limited the field of view.

Research has shown that peripheral vision is vital for assessing a scene in a sports context and this would tend to suggest that this would also be a vital consideration in combat. Face-mask eye apertures can reduce the wearer’s vision to something like 30% of its full potential laterally and 50% vertically (depending upon the fit of the helmet), effectively giving the wearer tunnel vision.† By limiting the wearer’s field of vision in this way, the face-mask helmet would paradoxically render him more vulnerable on the battlefield. Armoured fighting vehicles provide a useful analogy, for (in the days before external digital cameras) tank drivers and commanders would always prefer to travel with their heads protruding unless the risk of injury from enemy fire would make it foolhardy. Driving or commanding a tank through a periscope simply did not provide sufficient information about the environment around the vehicle.

This, then, is presumably the reason that Arrian specifies that only the officers and best horsemen (the two were clearly not the same thing!) got to wear them: they needed all their skill to control the horse, perform the manoeuvres, and dodge dummy weapons, whilst handicapped in this way.

Thus, just as face-mask helmets were not ‘parade helmets’ (the Romans had no such notion: soldiers on parade wore their full battle kit), they were also not intended for real combat. Rather, they offered a level of protection necessary during the cavalry training exercise which Arrian called the Hippika Gymnasia and, as such, there was an inevitable trade-off between their usefulness as a defence and the situational awareness of the rider.

Thus, just as face-mask helmets were not ‘parade helmets’ (the Romans had no such notion: soldiers on parade wore their full battle kit), they were also not intended for real combat. Rather, they offered a level of protection necessary during the cavalry training exercise which Arrian called the Hippika Gymnasia and, as such, there was an inevitable trade-off between their usefulness as a defence and the situational awareness of the rider.

*That’s about one every 50m if you lined them up along the Wall, which would be silly, but impressive.

† I’m grateful to Jurjen Draaisma of the Ala Batavorum for confirming (from practical experience) the limiting effects of wearing a face-mask helmet on peripheral vision.

You must be logged in to post a comment.